Will the U.S. Federal Reserve Finally Raise Its Policy Rate, and What Impact Will That Prospect Have on Canadian Mortgage Rates?

February 23, 2015Bank of Canada Governor Poloz Keeps the Market on Its Toes

March 9, 2015 We live in strange times. Today, five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields are lower, at 0.72%, than the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate, at 0.75%. In other words, you now earn less yield if you lend your money to our government for five years than banks earn by lending money to each other overnight.

We live in strange times. Today, five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields are lower, at 0.72%, than the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate, at 0.75%. In other words, you now earn less yield if you lend your money to our government for five years than banks earn by lending money to each other overnight.

This odd phenomenon matters to Canadian fixed-rate mortgage borrowers because their rates are priced on GoC bond yields. If the supply/demand balance that is helping to keep these yields at ultra-low levels stays relatively constant, today’s ultra-low mortgage rates are likely to remain in place for some time. But that raises an important question, which is being posed with increasing frequency around the world: Who is buying government bonds at these levels and why? The answer is important because understanding where today’s demand is coming from will help us evaluate the likelihood that it will continue.

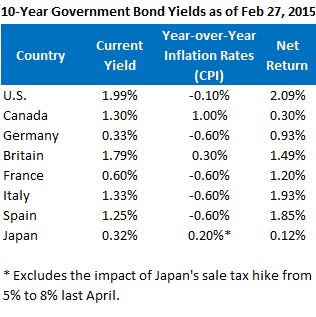

Let’s start by looking at the yields you can earn on a selection of 10-year government bonds as of last Friday, with inflation rates netted out:

At these yields, a lot of Freedom 55 retirement plans have been converted to Freedom 88 plans, but only because there is still plenty of demand for government bonds at these yield levels. These ultra-low yields might seem crazy at first glance. But inflation and growth rates are also very low and the bond market has a good track record of predicting where economic momentum is headed, so let’s not be too hasty in assuming that today’s bond buyers have completely lost their minds.

The following key players are helping to keep today’s bonds yields at these microscopic levels, and a more detailed look at their motives might surprise you by making their unyielding demand (pun intended) appear downright logical.

Central Banks Central banks buy bonds to provide economic stimulus for their domestic economies. When they buy large quantities of bonds, commonly referred to as quantitative easing (QE), this addition of incremental demand drives down their yields and lowers borrowing costs for business and consumers. Central banks typically buy bonds from banks, giving them added capital, which can then be leveraged up and lent out into the broader economy.

Central banks have the ability to print money to buy bonds, so technically, they can buy as many as they wish, although doing so gradually erodes the public’s confidence in their government’s ability to repay its mounting debt. That in turn undermines the purchasing power of that country’s currency. As central banks drive yields lower, investor appetites can diminish as the fake demand created by QE crowds out other legitimate sources of demand. As this happens, the central bank must absorb an increasing share of the supply of new government bonds. In an extreme case, such as Japan today, QE drives yields so low that the central bank effectively becomes the sole buyer of its government’s debt.

That isn’t the case in most countries, and certainly not in Canada, where our federal government has not engaged in any QE since the start of the Great Recession. But when other countries like the U.S., Japan and euro-zone members engage in QE, they soak up the available supply of bonds in large markets and push unmet demand farther afield, creating downward pressure on bond yields around the world, especially in small, open-market economies like ours.

Pension Funds Pension fund managers must balance two competing objectives when allocating their investment portfolios. They need to earn a return on their capital that keeps pace with the fund’s payment obligations and costs, but more importantly, they must ensure a safe return of their capital to have any money available at all.

Regulators require pension funds to allocate the majority of their capital to safe, low-risk asset classes, and AAA-rated government debt, such as we have in Canada, is viewed as the most risk-free investment available. Having the majority of their capital invested in safe asset classes also gives insurance companies a hedge to counterbalance the potential risk in the smaller, more aggressively invested portions of their portfolios.

The combination of regulatory requirements and the desire to conservatively hedge their portfolios ensures that the demand from pension funds for sovereign debt remains fairly constant, regardless of prevailing bond-yield levels.

Insurance Companies Insurance companies are also required to be conservative with the bulk of their investments, and they are attracted to the steady and predictable income streams that bonds provide because they can be used to offset the cost of claims.

Insurance companies also like to use bonds to match the duration of their liabilities. For example, life insurance companies buy long-term bonds that match the life expectancies of their policy holders. This feature is hard to replicate in other asset classes, so just as with pension funds, the demand for bonds from insurance companies is sticky resilient, even in an ultra-low-yield environment.

Banks Banks make most of their money by leveraging their capital and making a profit on the spread they earn between the cost of the money they borrow and the return on the money they lend. To keep banks from becoming overextended, regulators require that they hold a specific amount of capital on their balance sheets, which varies based on the risk profile of their investments.

Sovereign debt requires the least amount of regulatory capital, thus allowing banks to achieve maximum leverage. In some cases, this makes a low yielding sovereign bond with a minimal capital requirement more attractive, on balance, than higher yielding assets that tie up more of the bank’s scarce capital resources.

To cite one extreme example, euro-zone banks are not required to put up any capital when borrowing to buy euro-zone government debt, whereas they must hold capital that is equivalent to at least 8% of their borrowings when they are investing in corporate bonds. If you’re in the spread game, regulatory capital requirements are a very important element in your investment planning.

Reviewing the investment objectives of these large institutional players gives us a better understanding of why they are still buying up government bonds at today’s yields. But this only sheds light on the demand side of the equation, and of course, the available supply of bonds also has a huge impact on yields.

In our neck of the woods, the supply of new government bonds has been dropping for some time now. Both the Canadian and U.S. federal governments have significantly reduced their budget deficits, and this has reduced their need to issue new bonds. When that drop in supply is coupled with the non-yield sensitive institutional demand outlined above, yields stay at these microscopic levels even though everyman buyers wouldn’t touch government bonds with a barge pole.

Five-year GoC bond yields fell by six basis points last week, closing at 0.73% on Friday. Five-year fixed-rate mortgages are offered in the 2.59% to 2.69% range, and five-year fixed-rate pre-approvals are available at rates as low as 2.79%.

Five-year variable-rate mortgages are available in the prime minus 0.65% to prime minus 0.80% range, depending on the terms and conditions that are important to you.

The Bottom Line: Most of today’s demand for government bonds comes from central banks and non-yield sensitive institutional investors. This ensures a fairly consistent level of demand which, when combined with a diminishing supply of newly issued GoC bonds and U.S. treasuries, continues to exert downward pressure on our bond yields, and by association, on our fixed mortgage rates.